The U.S. has no solidified regulatory structure in place to ensure users know exactly where their digital information is going, and there is still no comprehensive federal consumer privacy law. Since 2020, most change has come from federal agency actions and a rapidly expanding patchwork of state laws: the FTC modernized the Health Breach Notification Rule to cover health apps and connected devices (2024 HBNR update); HHS updated the HIPAA Privacy Rule to better protect reproductive health information (2024 final rule); and the White House issued Executive Order 14117 directing restrictions on transfers of bulk sensitive data, with the DOJ beginning rulemaking (DOJ action). More than twenty states now have omnibus privacy statutes with rights like access, deletion, portability, and opt‑outs, with effective dates rolling through 2024–2026 (IAPP state tracker). Consumers are also demonstrably more privacy‑conscious: the FTC reports record U.S. fraud losses exceeding $10 billion in 2023 (FTC Data Book), and organizations report heightened expectations for transparency and AI safeguards (Cisco 2025 Privacy Benchmark), even as some findings remain consistent with earlier concerns about the use of their personal information.

A quick Google search will lead you down a path of headlines laden with words like privacy, spying, and listening. In practice, Echo devices are designed to send audio only after the wake word or a button press and provide clear light/voice indicators when active (Alexa Privacy). Amazon has also centralized optional settings that govern whether a small sample of recordings may be reviewed to help improve Alexa—you can turn this off at any time (Alexa Privacy Hub). While past reports noted human review and employees, current controls make such use opt‑in. Meanwhile, voice tech is shifting toward faster, more natural assistants powered by large multimodal models with sub‑second audio response times (GPT‑4o; Project Astra), which heightens the importance of on‑device processing and transparent privacy settings.

Amazon Alexa is designed to only start recording or “listening” after it hears a “wake word.” Wake‑word detection runs locally on the device, and you’ll see a visual indicator when Alexa is active (Amazon). If you want to minimize accidental activation, you can use the mic‑off button, review and delete voice history, set auto‑delete, or choose “don’t save recordings” in the Alexa app (Alexa Privacy Hub). Broader industry trends also favor privacy‑preserving compute—Apple’s Private Cloud Compute illustrates how requests that must leave the device can be processed on attestable servers with non‑retention as a design goal—reinforcing why clear indicators and on‑device-first design matter for voice assistants.

In using an Alexa-enabled device, Alexa may store audio recordings and text transcripts to provide the service; you can review or delete both via Alexa Privacy settings (controls). You’ll be forfeiting some conveniences by tightening Amazon’s data usage, but you can change defaults so audio isn’t saved at all, enable auto‑delete, or disable use of recordings to improve Alexa (device privacy). Note that even when you choose not to save audio, Alexa may retain text transcripts as needed to complete your requests or maintain features, and those transcripts are also reviewable and deletable in your history (Alexa Privacy).

Delete your voice recordings

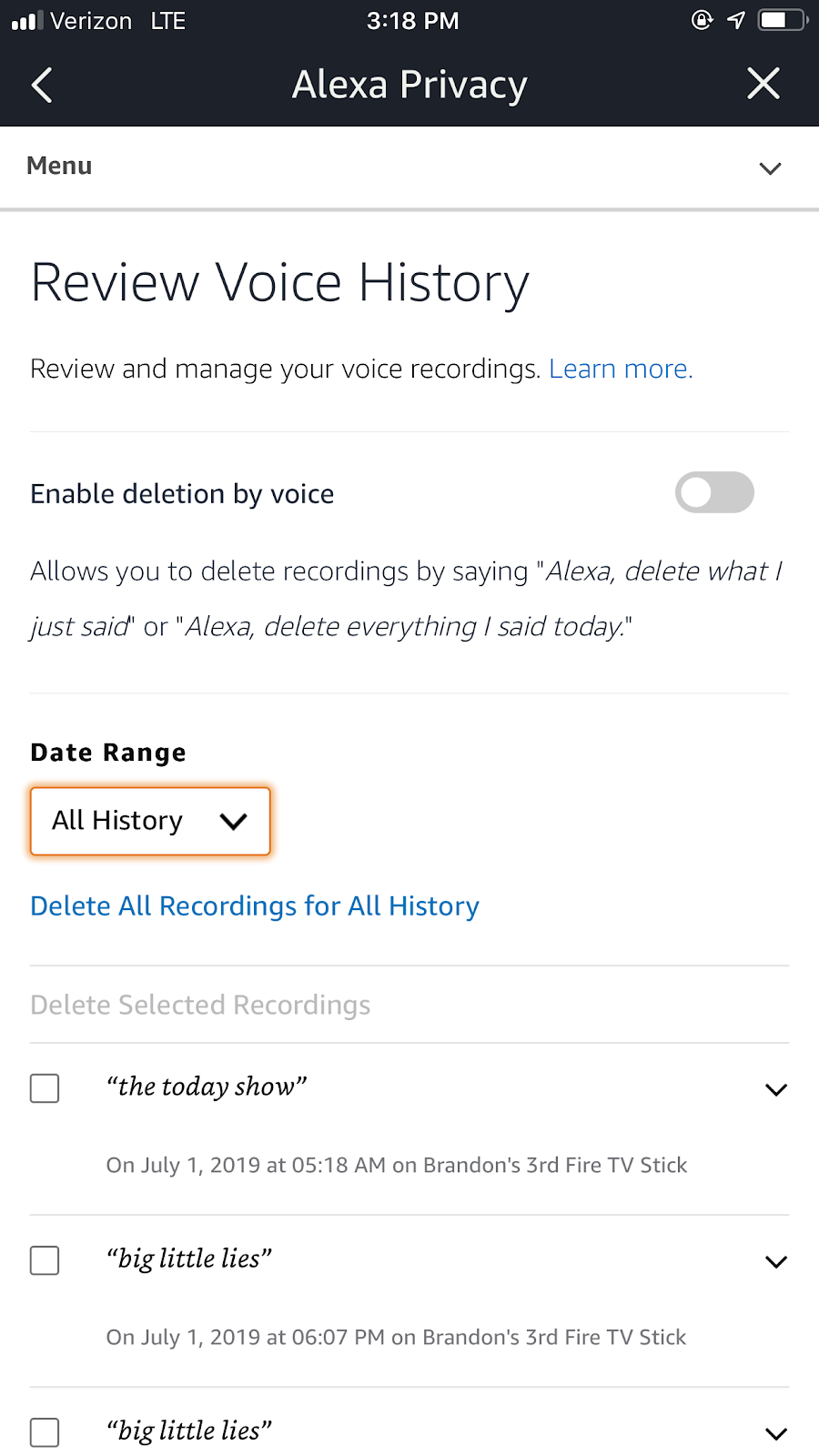

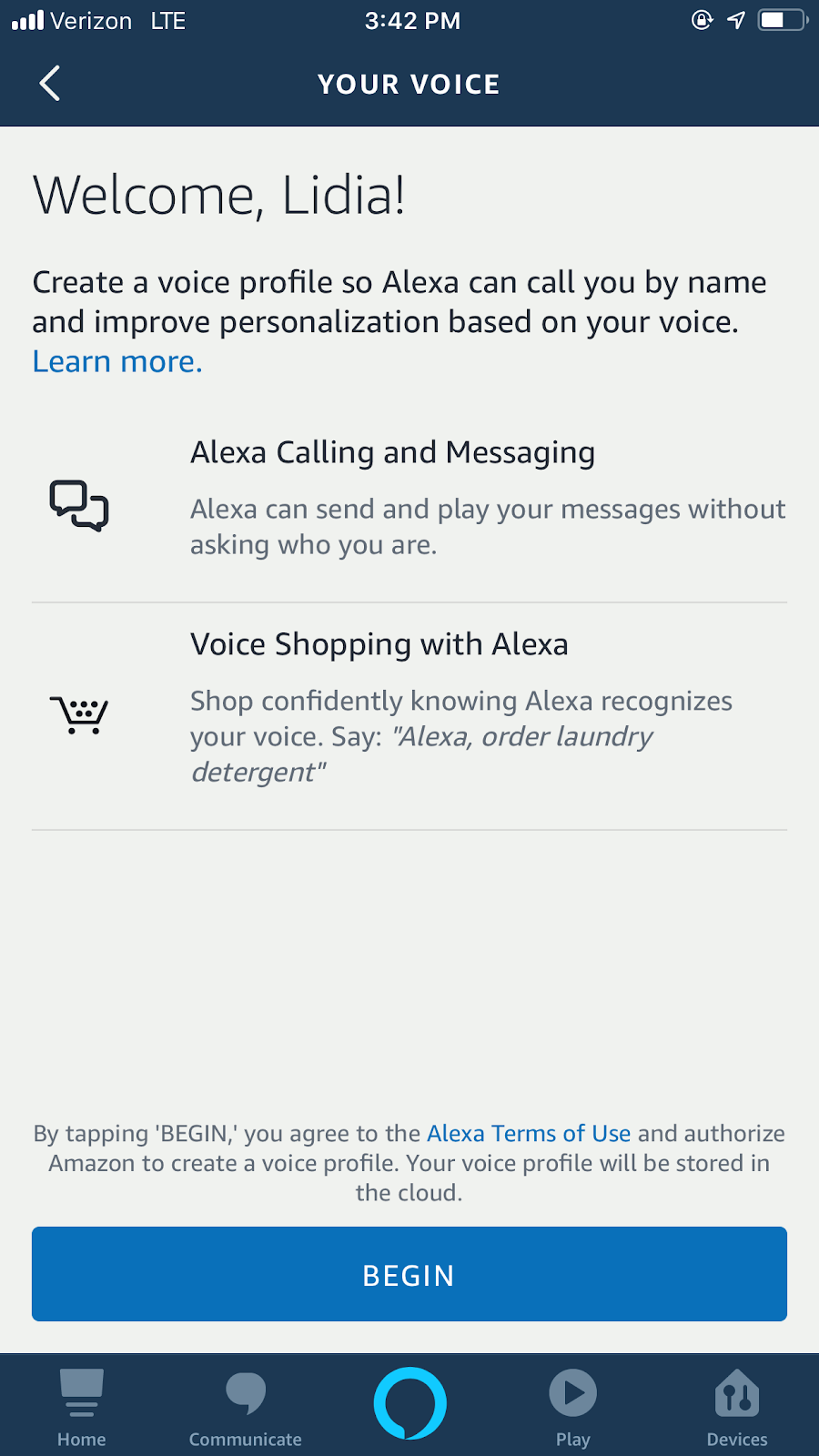

Amazon’s Alexa and Alexa Device FAQ says the more you use Alexa, the more it learns specific patterns in your voice to help better answer your requests. This is what’s called a Voice Profile — and you can always delete the information Amazon has gathered on your specific voice. Today, you can also choose how long Alexa saves voice recordings (keep until you delete, keep for a limited time, or don’t save recordings), turn off use of your recordings to help improve services, and delete by voice (for example, “Alexa, delete what I just said”) (Alexa Privacy Hub). Importantly, Alexa may store both audio and text transcripts; when you delete history, you can remove either or both. For families using child profiles, Amazon is obligated under an FTC order to delete certain children’s voice recordings and geolocation data and is prohibited from using children’s voice recordings and geolocation data to train algorithms (FTC order).

But this might not always be the case. Delaware Senator Chris Coons sent Amazon a letter in May asking why the company kept voice recording transcripts from Alexa. Brian Huseman, Amazon’s vice president of public policy, responded on June 28 in a public letter stating recordings remain stored on Amazon servers until a customer decides to delete them. As clarified in current materials, unless you change the default, Alexa generally saves voice interactions until you delete them; you can review and remove audio and transcripts and set auto‑deletion windows (Alexa Privacy).

If you’re unsure as to what is kept and what isn’t, you can always delete your voice recordings on the Alexa app or on the Alexa Privacy Settings page.

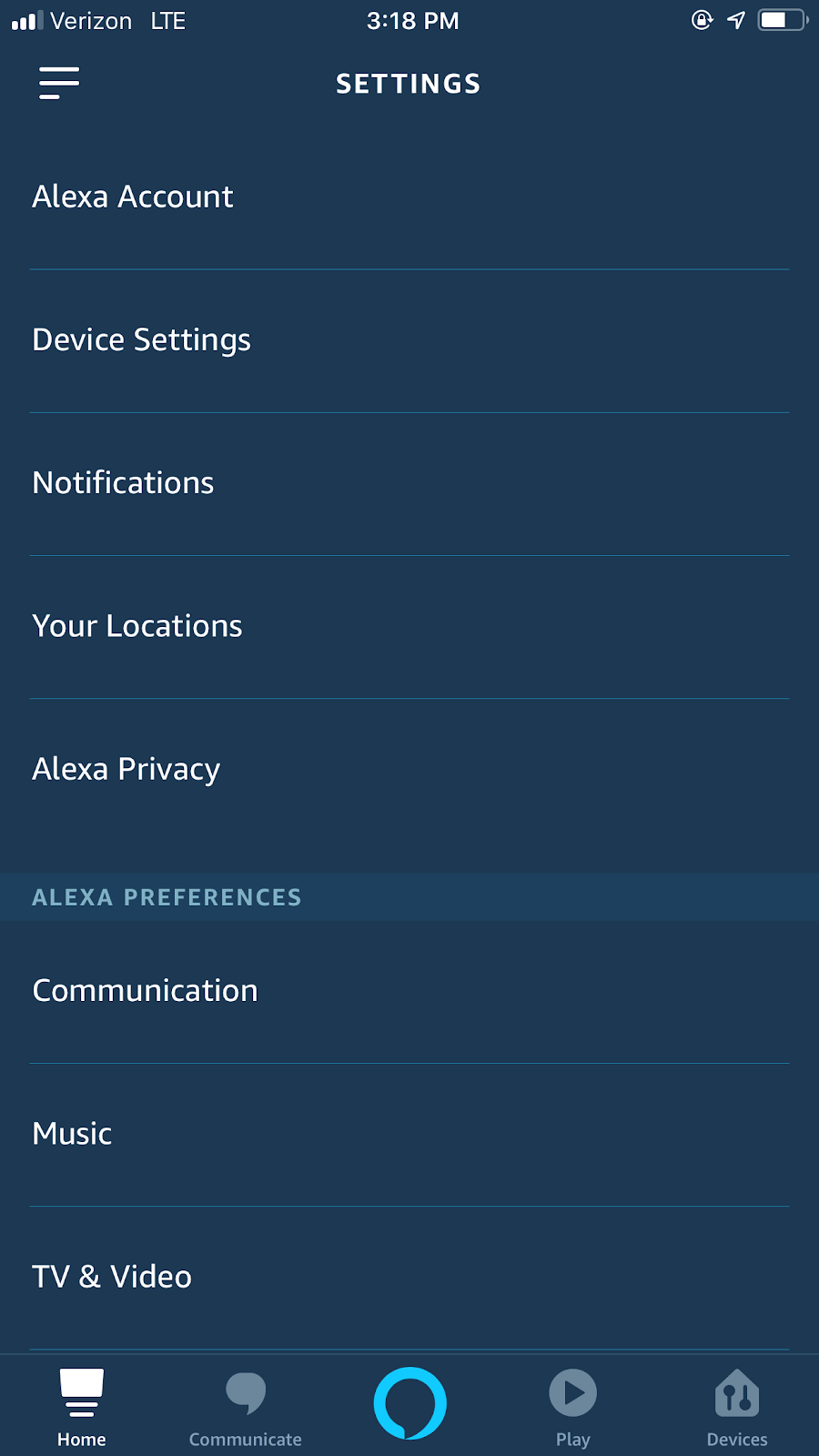

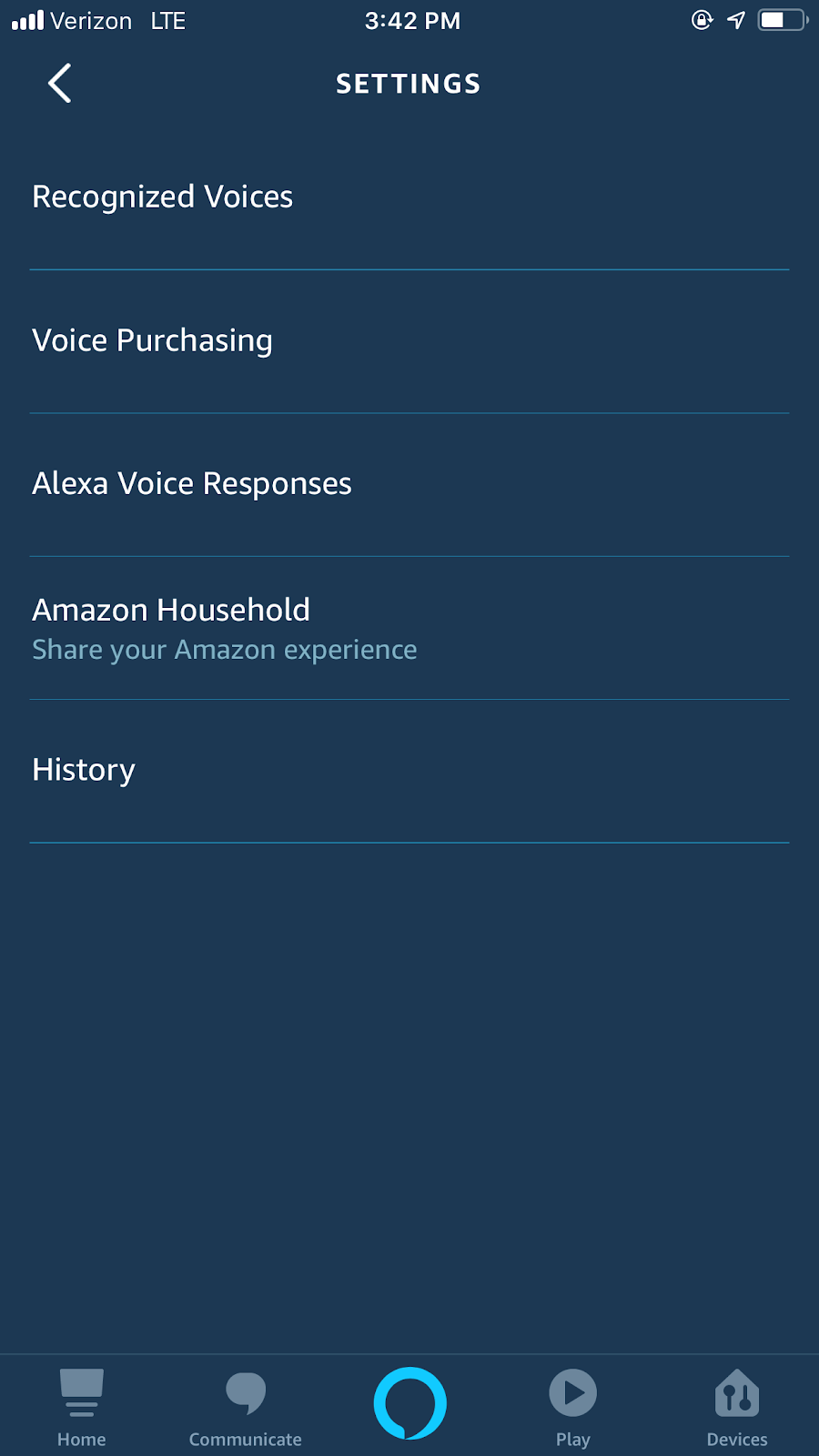

On the app, find “Settings” under the dropdown bar on the left hand side of the screen.

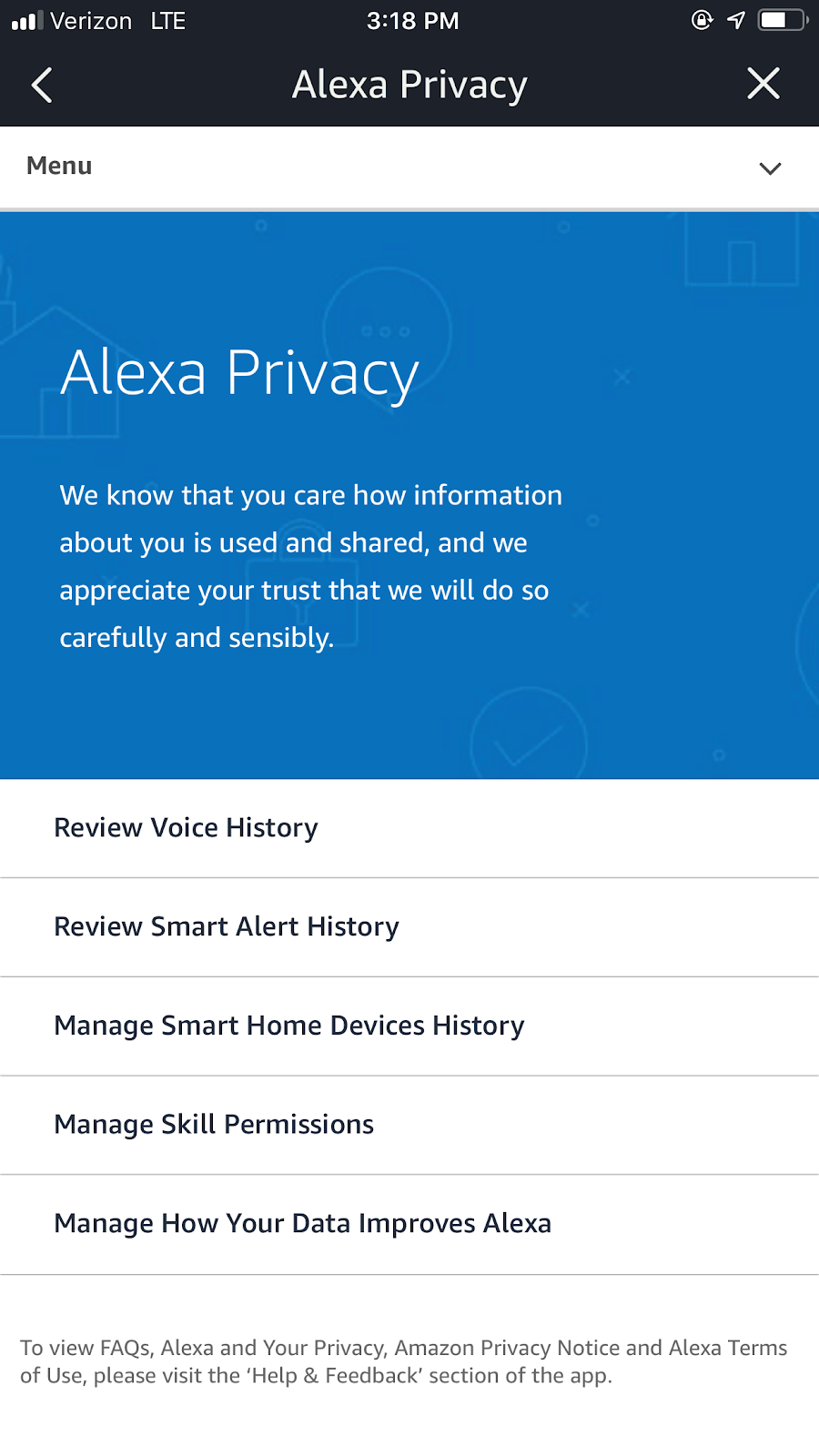

- Select “Alexa Privacy.”

- Under Alexa Privacy, select “Review voice history”

- Under voice history, you can search recordings by date and cherry-pick which ones you want gone, or you can delete them all at once.

And if you want to delete your voice profile:

- Go to settings

- Select “Alexa Account”

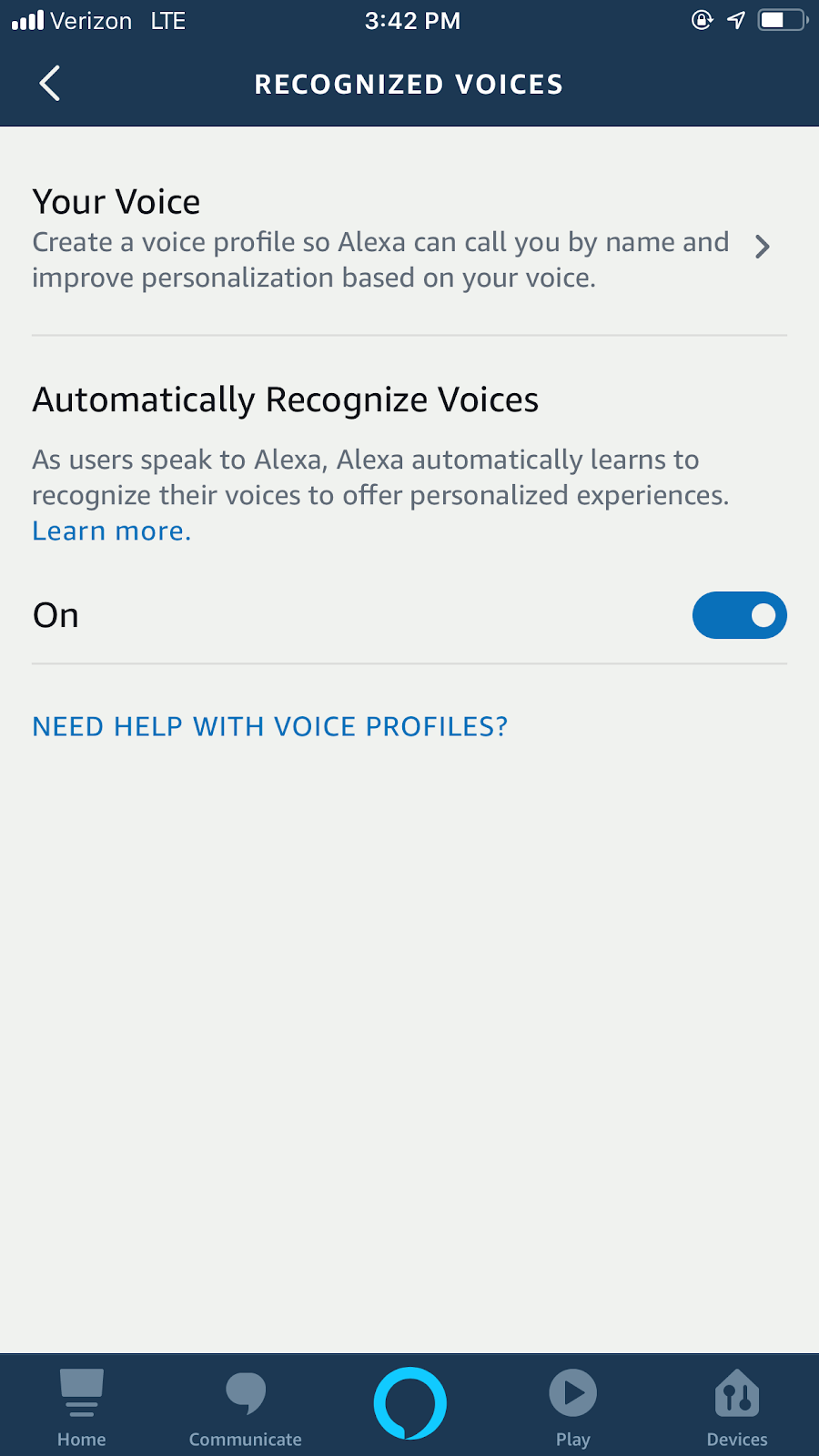

- Select “Recognized Voices”

- Choose “Your Voice,” and delete.

- You can also switch the recognition feature off.

Manage your search history

Amazon wants to know where you live to deliver packages to you, so if you frequent Amazon for everyday purchases and gifts, your location history might be unavoidable. If you want to disconnect your search history from Amazon’s servers, you can also delete your browsing and search activity; however, Amazon says blocking or rejecting cookies may hinder your experience (for example, you may not be able to add products to your cart). Amazon’s approach mirrors wider consumer trends since 2020: more people actively manage settings, reject non‑essential tracking, and expect clear controls and disclosures (EU tracker; UK Online Nation).

While you won’t hear any ads (targeted ones included) in Alexa’s voice on your device, if you have a Fire TV stick, Amazon may use your search history to target ads to you. One spokesperson previously told us if you play a song on Alexa, you may then see recommendations in the Amazon Music app for similar artists. The same applies if you order something using an Alexa voice command. You can change your ad preferences here, and consider setting shorter auto‑delete windows for activity where possible to reduce long‑term retention (Alexa Privacy).

Joshua Kreitzer, founder and CEO of Amazon advertising agency Channel Bakers, says Amazon is less invasive than companies like Facebook and doesn’t necessarily advertise based on individuals’ granular interests. “Amazon differs from, say, Facebook in the mindset that Amazon allows manufacturers and brand advertisers on their platform to target based on product shopping behavior,” Kreitzer says. “They’re not really strong in the landscape of interest-based targeting with their programmatic offering and or their search offering.”

Keep tabs on the skills you use

Amazon’s privacy notice says it’s “not in the business of selling it [information about customers] to others,” but it may share information with third parties. The Amazon spokesperson recited the Alexa and Alexa Device FAQ: “For Alexa Skills, when you use a skill, we may exchange related information with the developer of that skill in order to process your request, such as your answers when you play a trivia skill, your ZIP code when you ask for the weather, or the content of your requests. We do not share customer identifiable information to third-party skills without the customer’s consent.” In practice, most third‑party skills run on the developer’s own infrastructure, so data needed to fulfill a request is sent to that developer and governed by the skill’s privacy policy (Alexa Privacy).

Nothing is really taken without your consent — although the privacy policies of each developer may be hidden. You can manage skills permissions and settings — so before adding a skill, it might be worthwhile to check in on the exchange happening between the developer and Amazon. Skills must request specific permission scopes (for example, contact information, device address, or location) and handle denials gracefully (permissions; Device Address API). If a skill links to an external account, it must use standards‑based OAuth 2.0 over TLS and request only the scopes needed (account linking). Disabling a skill stops new sharing, but the developer may retain previously received data; developers are required to publish a privacy policy and provide a way for you to request deletion of your data (developer terms).

Coons responded to Huseman’s letter stating concerns about transparency: “What’s more, the extent to which this data is shared with third parties, and how those third parties use and control that information, is still unclear.” To evaluate a skill, review its permission prompts and linked privacy policy, and remember you can revoke permissions or disable the skill at any time (Alexa Privacy).

Privacy policies and terms of use agreements in general can get might have indirectly given us Amazon, Facebook, and Google. This is by design. The FTC watches over unfair trades and deceptiveness, and some experts say this causes companies to employ vague language to avoid wording their way into something that may seem deceptive, which, ironically, can result in deceptive levels of consumer confusion. “Just to start with the consumer perspective: I think it’s very difficult to convey what’s happening to your information and what people are learning about you through these types of service agreements and privacy policies,” David O’Brien, senior researcher Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, told Reviews.com for a story on no solidified regulatory structure in place. Recent enforcement underscores the stakes: the FTC has banned a data broker from selling sensitive location data without express consent (Outlogic settlement), took action against the sale of granular browsing data by an antivirus vendor (Avast settlement), and updated breach rules for health apps (HBNR modernization).

“Because of the way the FTC regulates, the tendency is if you’re a business, you want to write these things pretty broad, so that you don’t say something so specific that you might fall into the trap of having deviated from it in some way and perhaps deceived a consumer,” O’Brien said. Alongside federal actions, state privacy laws continue to proliferate (for example, Texas’s TDPSA and Washington’s My Health My Data Act), and federal policymakers are addressing cross‑border risks via Executive Order 14117 and the DOJ’s proposed restrictions (DOJ rulemaking). For voice experiences, the FCC clarified that AI‑generated voices in robocalls are illegal without prior consent, signaling stricter boundaries for synthetic speech (FCC ruling).

The bottom line: Amazon and your voice information

Amazon says it takes special note of privacy concerns, but that some of its data collection services provide more streamlined experiences for users. Cookies, for example, are used to help and streamline “1-Click” purchases and tailor ads to your preferences. For voice data, Alexa provides granular controls: you can review and delete recordings, set auto‑delete, choose “don’t save recordings,” and disable use of recordings to help improve services (Alexa Privacy). If audio isn’t saved, text transcripts may still be retained to deliver features, but you can review and delete those too. In the broader smart‑speaker market, trade‑offs differ: Google Nest does not save Assistant audio by default and offers a “Guest Mode” that avoids saving interactions (Nest privacy), while Apple’s HomePod emphasizes on‑device processing and does not retain Siri audio by default, with optional sharing of samples for improvement and per‑device deletion (Siri privacy; HomePod guide). Privacy expectations have risen since 2020, and organizations increasingly compete on transparent, privacy‑preserving AI and on‑device processing (Cisco 2025; Private Cloud Compute). Regardless, there are concrete ways to make your Alexa devices more private today: use the mic‑off button when not needed, set short auto‑delete periods, turn off “use recordings to improve services,” periodically audit enabled skills and permissions, and leverage the Alexa Privacy dashboard to manage both audio and transcript history (manage settings).